Rory Moore, BLUE’s Head of International Projects, discusses the decline of the sturgeon – the “king of anadromous fish” – in the UK and what BLUE is doing to bring it back.

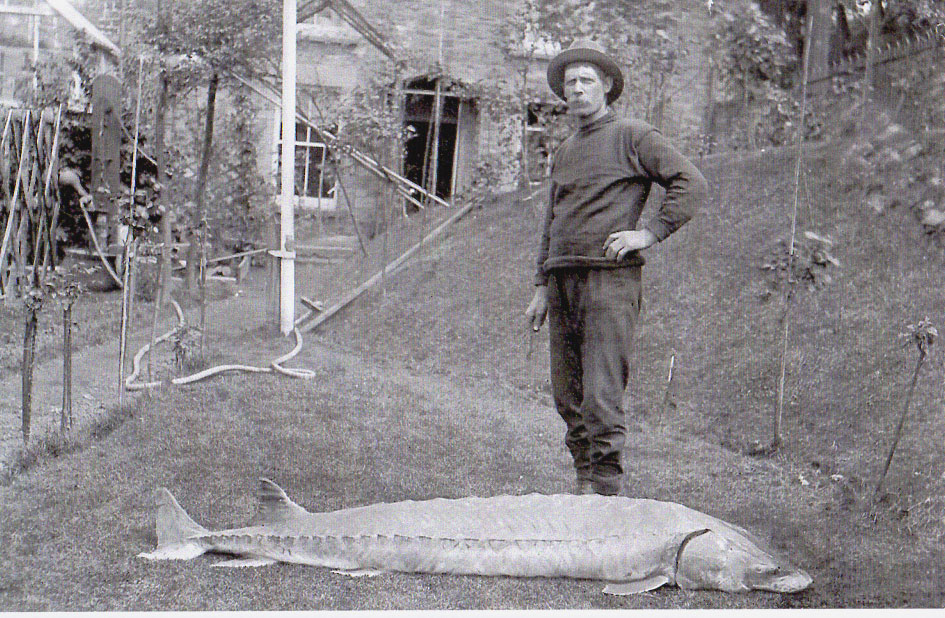

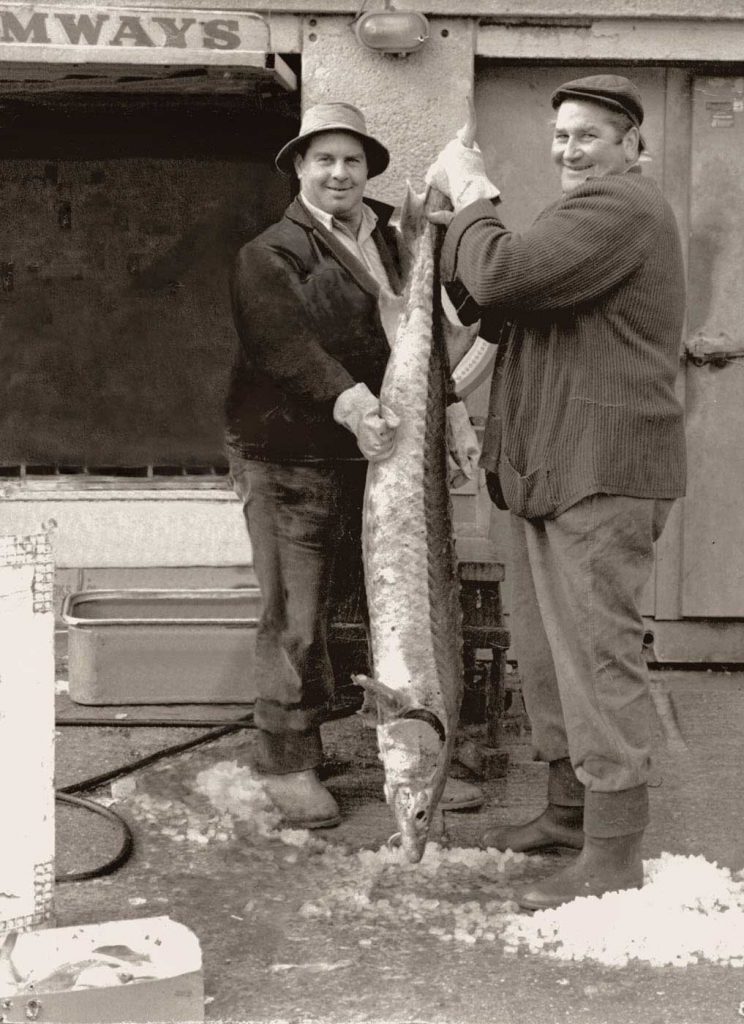

The largest ever fish caught by rod and line in a UK river was a giant 414-pound sturgeon, caught in 1903 on the river Severn. A few years later in 1911, another sturgeon was caught in the river Frome, a nine-foot monster of a fish. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, around 400 sturgeon were reported by anglers in the Severn, Wye, Usk, Thames, Medway, Towi, Teme, Tay, Forth, Tweed, Trent, Dee and Annan to name but a few rivers. The catches were always considered surprising. This was understandable, given that sturgeon are considered by the IUCN to be the most critically endangered group of species on the planet. In January of just this year the Chinese paddlefish, a close cousin of the sturgeon, was declared extinct.

However, the state of the sturgeon population was not always this poor. The European sturgeon or common sea sturgeon, which is native to UK waters, was once one of the most widespread sturgeon species, migrating up rivers throughout Europe in great schools to spawn. Most sturgeon are anadromous, meaning they live much of their lives in saltwater, but migrate up freshwater rivers to spawn. This 400 million-year-old prehistoric marvel of nature was considered so important that it was granted ‘royal’ status by Edward XI in the 14th century. A decree still exists that any UK captured sturgeon should be offered to the Crown. The sturgeon is the king of anadromous fish.

Archaeological evidence suggests that UK sturgeon strongholds were first devastated by Saxon river fish-traps over a thousand years ago. The sturgeon were prized for their meat and caviar, as they still are to this day. Anglo-Saxon overfishing and river habitat destruction were early signs of what lay ahead for sturgeon and other anadromous fish such as shad and salmon, and catadromous fish such as eel. Catadromous fish act the opposite to anadromous fish, spending much of their lives in freshwater, and migrating to the seabed to spawn.

Sturgeon are highly vulnerable and susceptible to anthropogenic abuse. They are large, slow-growing fish, requiring ten to 20 years to reach sexual maturity. They reproduce only periodically, laying thousands of delicate eggs on upriver gravel beds where the water is cool and oxygen content is high. They require unpolluted estuaries, where adults feed in the mud on molluscs and crustaceans, and juveniles adjust their bodies from freshwater to salt. As late adolescents and adults, they spend much of their life in the lower reaches of estuaries and in shallow coastal waters. Given these traits, it is remarkable that these fish are still battling for survival in a world of intensive agriculture, overfishing, water insecurity and changing climate.

Fortunately for the sturgeon, they are not in this battle alone. All over the world, conservationists are working to bring sturgeon populations back to health by restoring habitats, releasing genetically diverse fingerlings (juvenile sturgeon), banning fishing and connecting communities with the “dinosaur fish”. This battle is not just about sturgeon; it is about restoring healthy spawning and nursery habitats that benefit a diverse number of species. It is about the way that these fish interact with the environment, removing decaying organic matter from the sea and riverbed, and their ecological symbiosis with other fish such as Shad.

Arguably the greatest sturgeon conservation success story of all time played out in the US in the Shawano river, Wisconsin. In the 1920s the Great Lake sturgeon faced extinction from overfishing and habitat destruction. Conservationists rallied to save the fish, creating passes around dams, restoring gravel beds for spawning, breeding and releasing millions of juveniles back into the wild. Their efforts were rewarded within just a few decades when sturgeon began to return to their spawning grounds. Now locals, tourists and ecologists flock to Shawano each spring to watch the huge fish laying their eggs in the rocky shallows. This one weekend in the year generates over $350,000USD in revenue for the local economy and attracts thousands of conservation volunteers. The restored gravel beds provide habitat for a diversity of aquatic life and the sturgeon maintain a well-balanced ecosystem by feeding on introduced species such as gizzard shad.

In Europe, the European sturgeon is listed as one of the five priority fish species under the Habitats Directive’s protective measures. The last spawning ecosystem for European sturgeon is the Garonne river and Gironde Estuary in southwest France. French conservationists have been restoring breeding and feeding sites for sturgeon, releasing tagged, genetically diverse fingerlings and improving water quality in the aquatic environment. Similar programmes are under way in the Rhine and Elbe. All of this work is now consolidated under the 2018 Pan European Action Plan for Sturgeon. This transboundary, collaborative approach is key for the survival of a fish that migrates thousands of miles to find ever scarcer spawning and feeding grounds. In fact, it is understood that between five to ten per cent of adolescent sturgeon actively seek new rivers to spawn, instead of returning to their maternal river. This evolutionary trait to expand their range acts to diversify the genetics of the population.

Which brings us back to the UK. In recent years, fishermen on the south coast of England have been catching young tagged French sturgeon in their nets. Although it is unlikely that sturgeon have spawned in UK rivers for many years, it is becoming clear that sturgeon originating in European rivers have been migrating to the UK to look for suitable feeding estuaries and spawning rivers. The majority of the fish now being reported in our rivers are caught at the expected spawning time, often full of eggs, suggesting their intent to spawn in the UK. Records suggest that sturgeon have been returning to the UK to do this over the past few hundred years at least, and likely before these records began.

To nurture the sturgeon, Blue Marine Foundation (BLUE) has formed the UK Sturgeon Alliance with the Severn Rivers Trust, Zoological Society of London, Institute of Fisheries Management, and Nature at Work with collaboration from the Environment Agency. The Alliance exists to:

- ensure that UK rivers and estuaries are in fit state to accommodate critically endangered European sturgeon;

- restore suitable sturgeon spawning and feeding habitats;

- improve connectivity of estuary and river habitats to enable fish migration;

- protect European sturgeon in UK waters;

- prevent non-native sturgeon originating from the pet trade from escaping into the wild;

- increase public awareness and pride of UK sturgeon; and

- explore ways under IUCN Reintroduction Protocol to restore sturgeon numbers in the UK.

The Alliance supports a BLUE initiative to introduce the terrestrial rewilding movement to UK marine environment. According to the United Nations, degradation of land and marine ecosystems could negatively impact the well-being of 3.2 billion people and cost as much as ten per cent of annual global gross domestic product in loss of species and ecosystem services. The picture in the UK is no different. We currently “protect” ecosystems that are already stripped of biodiversity including sturgeon and, as time goes on, we lose the concept and the ecosystems services of healthy, abundant aquatic ecosystems forever. Rewilding approaches could be readily applied to the ocean and rivers to assist recovery, particularly when coupled with highly protected areas that offer much-needed refuges to vulnerable and depleted marine life.

BLUE plans to work closely with counterparts on the continent, exchanging knowledge, skills, experiences and genetics – a truly transboundary approach for a truly transboundary fish. As a recent paper in Nature highlights the recovery of humpback whales, elephant seals and other marine species through habitat restoration and protection, there is no reason why the UK shouldn’t be raising its game to facilitate the recovery of one of the greatest fish on the planet – the sturgeon. To do so would not only prevent the extinction of a UK species but would improve the health and increase aquatic diversity of our rivers. Rivers and fish that we should be proud of as a nation.

Cover photo caption: June 1906 in the 100ft river this Sturgeon fish was caught by hand by a group of men when the fish got stranded on a silt bed opposite the Crown Public House, the tide was so low that the men was able to walk out to the silt bed and carry the Sturgeon back to the river bank and load it onto a cart to be taken to Mr P F Tow the fishmonger at Ely.Credit: Pymoor Cambridge Community Archive Network.