A new report[1] published this week shows that EU-affiliated purse seine fishing fleets in the Indian Ocean have been turning off their satellite tracking systems for long periods of time, often in areas where the highest levels of tuna catch have been reported and in apparent contravention of numerous EU, national and international laws. More than three quarters of the vessels studied “went dark” for longer than a month at a time, with one operating without its Automatic Identification System (AIS) switched on for over 100 days straight. The report has been published in advance of next week’s annual meeting of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) – the intergovernmental body in charge of managing the region’s shared tuna stocks, two out three of which are currently overfished[2] and on sale to British consumers in most large supermarkets.

The publication of the report, which was commissioned by Blue Marine Foundation and undertaken by OceanMind, coincides with confirmation from an ‘access to documents’ request submitted by Blue Marine that the European Commission is investigating “the existence of potentially unlawful long gaps of the Automated Identification System (AIS) on board of Spanish and French vessels in the Atlantic and Indian ocean”.

This follows a complaint submitted by Blue Marine to the Commission in 2023 which highlighted extensive AIS gaps exhibited by French and Spanish-owned tuna purse seine fleets operating in both oceans over many years[3]. The complaint also referenced a peer-reviewed article by a lawyer working for Blue Marine’s Investigations Unit which found that EU-owned vessels operating in the Western Indian Ocean switching off their AIS for extended periods of time were likely breaching international, flag state and coastal state laws[4].

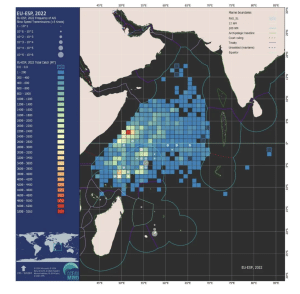

The new report analysed the AIS use of the entire EU-owned Indian Ocean tuna purse seine fleet (including those operating under flags of convenience, such as Oman, Tanzania, Seychelles and Mauritius) from January-October 2023. Catch and effort data are reported by these fleets to the IOTC, and the report compared the location of this catch with the fleets’ AIS usage for 2021 and 2022. The report points to huge volumes of tuna being caught in areas with no AIS transmissions at the slow speeds associated with fishing activity. This is particularly the case for the Spanish-owned vessels, and in 2022 the Spanish fleet reported over 5,000t of catch in an area with zero slow-speed AIS transmissions. There have been instances of misreporting of catch-effort data by the EU in the past[5], but that would not negate the need to answer for this new dataset submitted to the IOTC.

Frequency of AIS transmissions at slow speeds (<5 knots) overlaid on the Spanish fleet’s reported catch, 2022 (Source: OceanMind)

Since Blue Marine submitted its legal complaint regarding breaches of AIS laws, the European Commission has been responsible for the weakening of several aspects of AIS laws, both through amendments to EU law, and through fisheries law reforms that coastal States, such as Mauritius, were pressured by the Commission into adopting.

In addition to being under investigation by the European Commission, this tendency of Spanish and French vessels to “go dark” for months at a time also jeopardises their coveted Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certifications. Following objections by Blue Marine and others, conditions have been placed upon several MSC certifications, requiring vessels to demonstrate that there is “no evidence of systematic non-compliance in the use of the AIS”[6]. During one such objection process, a representative of the fishery admitted that vessels operate “dark” for commercial advantage[7]. However, doing so endangers lives at sea and reduces fishery transparency.

This comes at a time of increased scrutiny for the Spanish and French-owned fleets who will be represented by the EU at the annual meeting of the IOTC starting on Monday 13 May in Bangkok, Thailand. In 2023, a new IOTC conservation and management measure was adopted[8] to curb the use of drifting fish aggregating devices (FADs) – a type of harmful fishing gear used by the same “dark” Spanish and French fleets to catch already-overfished juvenile tuna in their millions. Despite a clear majority of IOTC members voting in favour of the new measure, the EU formally objected to it[9] making it non-binding and forcing Blue Marine and BLOOM Association to take legal action against them, as the objection is in breach of EU law and, in particular, in breach of the precautionary principle[10].

Jess Rattle, Head of Investigations at Blue Marine Foundation, said: “We’re glad to see that the European Commission is undertaking an investigation into these fleets that go dark for months at a time in an ocean where tuna stocks are overfished and where EU vessels continue to use destructive drifting FADs to wipe out millions of juvenile tunas. We hope that this is a sign that the EU will finally start taking responsibility for the behaviour of its distant-water fleet, and that this will translate into greater transparency on the water, followed by a moratorium on the use of harmful drifting FADs”.

Image credits: Alex Hofford/Greenpeace

[1] OceanMind (2024) IOTC Catch-effort assessment and AIS usage in the Western Indian Ocean, 2021-2023. Available:

[2] Blue Marine Foundation’s statement in advance of the IOTC meeting is available here: https://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/2024/05/02/statement-in-advance-of-the-28th-session-of-the-iotc/

[3] Previous reports undertaken by OceanMind are as follows:

- Automatic Identification System (AIS) usage by Spanish and French-flagged vessels (2020)

- IOTC catch-effort assessment, and AIS usage by flag-states in the Western Indian Ocean, 2016-2020’ OceanMind (2022)

- AIS usage by flag-states in the Indian Ocean 01Jan2021-31Aug2022 (2022)

- Mauritian Purse Seine Vessels Risk Assessment (2023)

- AIS Utilisation in ICCAT by European-Flagged Fishing Vessels between 2018-2021 (2023)

[4] P Bunwaree (2023). The Illegality of Fishing Vessels ‘Going Dark’ and Methods of Deterrence. International & Comparative Law Quarterly. Available: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-and-comparative-law-quarterly/article/illegality-of-fishing-vessels-going-dark-and-methods-of-deterrence/8E5D5C30A15C91BF17423ED1EF6EE0E2

[5] J C Báez et al. (2022). Review of the time-series (2016-2021) of catch-and-effort for Spanish purse seiners operating in the Indian Ocean. Available: https://iotc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2022/11/IOTC-2022-WPDCS18-INF01_-_EUESP_PS.pdf

[6] See, for example, the ANABAC Indian Ocean Purse Seine Skipjack Tuna Fishery Final Draft Report, available: https://fisheries.msc.org/en/fisheries/anabac-indian-ocean-purse-seine-skipjack-fishery/@@assessments

[7] J McKendrick QC (2022). Decision of the Independent Adjudicator. Marine Stewardship Council Independent Adjudication in the matter of an Objection to the Final Draft Report and Determination on the Proposed Certification of the AGAC Four Oceans Integral Purse Seine Tropical Tuna Fishery (Indian Ocean).

[8] K McVeigh (2023). Deal to curb harmful fishing devices a ‘huge win’ for yellowfin tuna stocks. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/feb/08/deal-to-curb-harmful-fishing-devices-a-huge-win-for-yellowfin-tuna-stocks

[9] See: https://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/2023/04/12/statement-following-the-eus-objection-to-iotc-resolution-23-02/

[10] See: https://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/2023/05/10/legal-action-launched-against-the-european-commission-for-its-objection-to-iotc-fads-resolution/