Saturday 25.11.23.

11 pm. Four of us arrived at Lauwersoog, a major fishing port in the north of Holland, in Emilie Reuchlin’s blue camper van. It was icy cold and clear. Around the dock were two distinct types of fishing vessels, large trawlers used to fish far out in the North Sea and smaller prawn trawlers used to fish around the Wadden Islands. Dotted in front of some of the company offices along the dock were some large round boulders brought down by glaciers at the time of the last Ice Age. Emilie, co-founder of the Dutch charity, Doggerland Foundation, explains that Wadden Sea fishermen hunting for flatfish would clear these boulders from the seabed to avoid losing their nets and land them for use in walls or roadblocks. The Ice Age connection had brought us here too: for our self-appointed task was to journey out and survey the surface of what was then the land bridge between the British Isles and Continental Europe, until it was drowned by rising seas around 8,000 years ago and eventually became known as Dogger Bank.

Every school child of my generation was taught that Dogger Bank was where fishermen went to catch the fish on our plates. Now part of it was an area protected from trawling and dredging we wanted to know if it was recovering. What were the chances of restoring it to a time when fishermen caught halibut there the size of a man, when common skate the size of dinner tables flapped over the sandbanks, or a migrating sturgeon of 262 kilos was trawled up on Dogger Bank and commemorated in a photograph on the wall of a Lowestoft pub, back in 1925? Then the North Sea was once the most productive sea in the world and the Dogger was at its heart.

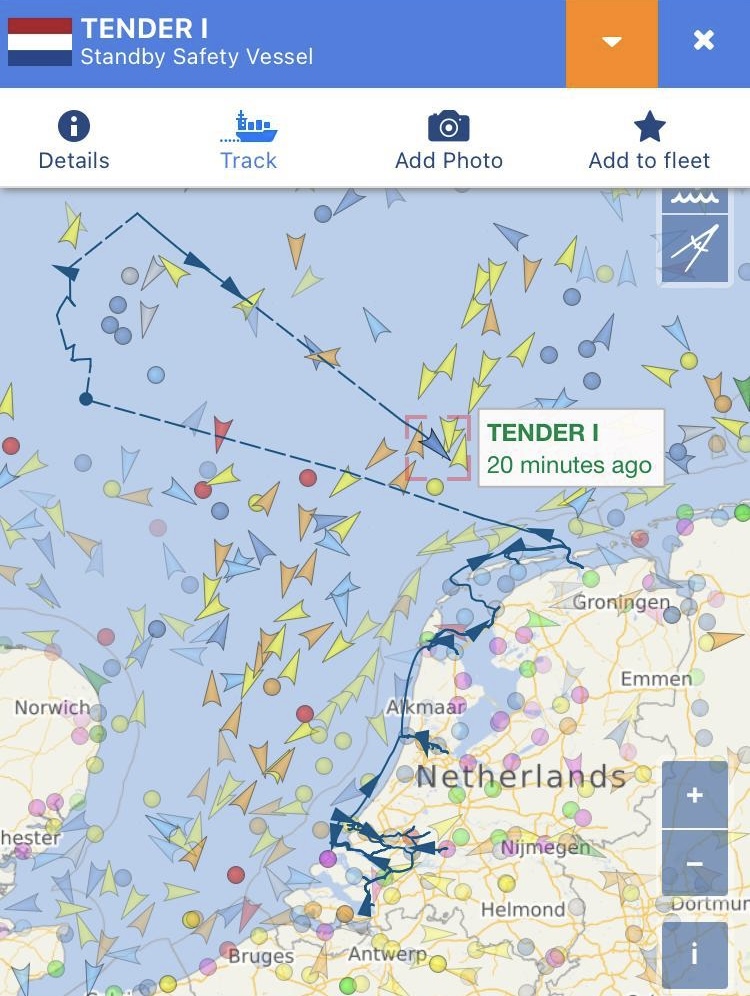

We drove around the sizeable harbour and found our vessel, the MS Tender, a robust-looking 45-metre standby safety vessel built in 1954 and carefully nurtured and improved ever since by its skipper and owner Frank Loonstra. He and his crew and our other NGO coalition partners from Ark Rewilding Foundation are already there. We were shown our bunks and had a brief cup of tea as it would be an early start. The high tide was just after 8 am and that is the safest time to pass through the shoals between the Wadden Islands just offshore.

Marine Traffic map showing the expedition route.

Sunday 26.11.23

7 am. The crew and Robin and Lisa from a specialist firm loaded and carefully stowed the bottom-towed camera equipment on deck which took about an hour. Then we headed off out to sea, disturbing the herons from the sea wall at the harbour mouth. The weather reports had been changing hourly and it was even harder to know what it would be like where we were going which is about 20 hours steaming from the Dutch port – and only about seven hours from the UK. The Dogger has its own self-contained weather system, as anyone who listens to the BBC’s shipping forecast knows. As we passed out through the Wadden Islands it was rough with the tail of a storm which passed through a day or so before. There were Dutch oil rigs just offshore. So close to the shore is the oil and gas development that it has affected people’s houses with subsidence and the industry is not popular in this part of Holland because promised compensation has never turned up, Emilie explains. She shows me a map of the enormous extent of oil and gas development in the Southern North Sea, mainly south of Dogger but also on the bank itself, where we are going. And on Dogger itself, in the UK sector, there were already many large wind turbines and more wind farms under construction – a task which rolls on in all weathers. We motored through the waves all day on a big green sea dotted with storms and rainbows. Out beyond the islands we began to see birds that we only see in summer on the west coast of Britain: a puffin, a guillemot. Fulmars and kittiwakes followed the boat hopefully. Gannets soared and dived. We got to our bunks early as it will be an early start. Some of our number were already feeling seasick. I was greatly relieved that I had put a Scopoderm patch behind my ear before leaving port.

Oil Development off Wadden islands. Credit Charles Clover

Monday 27.11.23

4am. We woke, after 20 hours of steaming, just as we reached the Dogger at a place called Boulder Bank. The sea was suddenly astonishingly calm. We found we were not alone. Roughly a mile behind us were the yellow, red and white lights of a gas and oil rig in the Trent field. A few miles to the north was a rig in the Cavendish field. To the east were the lights of a wind farm now under construction. Frank was on the bridge and identified the moving lights far off ahead of us in the dark as a large vessel with a 13m draft, probably a wind farm supply vessel. A drone flew by and had a look at us, which was unnerving. Where is it from? Most likely it had been sent to check us out by a security detail on the Trent rig, which was closest to us and all lit up. As it got light I noticed that the colour of the calm sea was a milky blue, thanks to the suspended particles churned up by overnight storms.

This was our introduction to the largest marine protected area in British domestic waters, designated a “special area for conservation” which – though the UK government is careful never to say it – is internationally assumed to mean that conservation is the prime purpose of the area. A shallow sandbank nearly the size of Belgium, Dogger Bank has the same protection on paper in the waters of Holland and Germany too, though only Britain, as yet, has banned trawling and dredging. In the Danish sector it has no legal protection at all and that section is being drilled for oil and gas.

By chance we came to look at the state of the seabed in the British sector just a couple of days before Rishi Sunak announced, at COP28, a massive £11 billion deal between the energy firms RWE and Masdar that will make the wind farm on Dogger Bank the largest in the world. Rishi Sunak has also faced criticism for scaling back various pledges to help the UK reach net zero by 2050 and vowed to “max out” oil and gas reserves via North Sea drilling licences. About a third of those licences are expected to be granted in marine protected areas, such as Dogger Bank. Are all these ambitions compatible with nature conservation and the recovery of the degraded, overfished Dogger Bank ecosystem that the ban on trawling and dredging was meant to achieve? The British government seems to think so. We had come to find out how much crucial habitat for marine life survives in this industrialised seascape and to see what further scope there might be for its restoration – either by being left alone or by the reintroduction of long-absent reef-building species such as horse mussels.

Dogger Bank seabed survey undertaken by Doggerland Foundation. Credit: Danny Copeland c/o Blue Marine Foundation

7 am. Dressed in all-weather gear with lifejackets and helmets, the crew, Emilie and the technical consultants were trying to assemble the camera rig. There was a short delay. They found that one of the cables they have brought, the longer one, does not plug into the camera housing they have fixed to the cage. Luckily they have another camera and another cable, though it is shorter. Only 50 metres long. The depth here is 48 metres. They start again. The news comes through that it will work, we are going to get away with it. The camera is lowered slowly to the seabed. The live feed beams to laptops on the bridge and in the mess. We get down to recording what we see on dauntingly complicated Excel forms.

9 am. The good news though was that down on the seabed the visibility was surprisingly clear as we began the first of eight long transects planned by Emilie. At first the surface was what you might expect of a sandbank: mobile, wave-sculpted sand dunes with the odd worm burrow and here and there the odd sandeel or flatfish, probably plaice, and a few bryozoans, such as hornwrack, a colony of animals frequently mistaken for seaweed. On the next transect that we named Blue Half Moon, the seabed was much more interesting and varied, with far more shells, gravel and stones. There was much more new life on the sand, mud and gravel: crabs, sponges, razor clams, a sea urchin, an anemone and then a succession of patches of dead man’s fingers – a kind of soft coral that takes five to ten years or so to grow to 10 to 15 cm, so this was relatively undisturbed ground. The appearance of more and more of this soft coral was greeted with cries of excitement from the team. There were patches– by no means all of each transect – that were brimming with life.

There were small fish – a dragonet, a blenny, some flatfish, what looked like a red mullet. There was the empty egg-case of a catshark. Emilie spotted a mermaid’s purse – the egg sac of a skate or ray – attached to a stone. She also spotted an ocean quahog, a kind of edible clam capable of living for centuries. Its growth rings have been used to confirm changes in the climate. Wikipedia tells us the oldest quahog ever recorded, found in 2006, began life in the reign of Henry VII. It was 507 years old. It had had a much slower growth rate during the little Ice Age from 1550-1620.

Noon. Emilie’s elaborate monitoring plan meant that some of us had been chosen to observe what was going on at the surface at each location. The profusion of bird life continued to surprise us. My non-scientific impression was that the birds were more plentiful where there was the richest habitat beneath. Along with the kittiwakes and fulmars that had followed the boat since it left port, we recorded gannets, great black backed gulls, herring gulls, common gulls, guillemots, puffins and the occasional little auk, a winter migrant from the Arctic. Suddenly, in a raft of gulls, there was the head of a grey seal, curious and untroubled by being seventy miles or more from the English coast. It was not the only grey seal we saw. The ease with which grey and common seals can forage contentedly a long way from shore, diving to depths of hundreds of feet, may seem surprising until you reflect that they are fish eaters, living on sand eels, whiting, cod, haddock and flatfish. Dogger is where those species still are found, though not in the profusion they once were. The one significant species we looked out for but did not see was the harbour porpoise, known to frequent the banks, but as the waves got up we had few opportunities to spot its dimpling dorsal fin.

Grey seal on Dogger Bank, credit Charles Clover

Also located on that first day – but not surveyed for fear of entangling the camera cage – was the unidentified wreck of a 60-metre long vessel, standing well above the sand on the sonar. Wrecks are a refuge for all sorts of species, notably fish, and are therefore perfect sites from which to begin species and habitat restoration. Emilie took co-ordinates to come back and dive it in the summer. We visited the site of another wreck on the chart but it was barely visible above the seabed, having almost collapsed into the sand. This one had all but gone and was probably not much use.

7pm. After a day of calm seas and low wave heights the wind rose rapidly into the darkness and it was Force 7 and rising by the time we went to our bunks. The wave height that night, I’m told, was up to around five metres. The ship was surging forward confidently and safely into the swell but corkscrewing as it did so. Few of us slept for more than a couple of hours for the sound of things banging around and the feeling that the rolling of the ship was going to tip us out of our bunks. Eventually, around 3 am, I identified the locker in my cabin where an airline bag was banging from side to side and stuffed a couple of life preservers either side of it so I could get to sleep.

Tuesday November 28.

At around four in the morning the barrelling and banging subsided. By dawn, just after eight, we got the camera in the water again at a place called, appropriately, North Rough. The height of the waves was hovering around the maximum that the camera rig could work in – 1.5 to 2 metres. The first transect was aborted because of low visibility due mud and sand stirred up by the storm. Steaming on we found clearer water and were able to accomplish several long transects of promising ground before the wind rose again.

As we did so we realised that what we were looking at on these long transects was terrifically good news: there was ground here, in patches, that was recovering well and which deserved to be left alone to go on accumulating species, forming firmer reefs and tying down carbon now the previous threat, trawling and dredging, has gone away. Yet what was worrying Emilie was that an old threat had been replaced by a new one: these areas of prime habitat lay right in the path of wind farm development – with oil and gas following on behind.

The virtue of Dogger Bank for a wind farmer is the same as it is to a fisherman, it is relatively near the surface. The UK has decided that it prefers its wind farms out at sea and the Dogger is shallow and vast and therefore an economically viable place to install wind turbines. An enormous increase in wind farm capacity is needed to de-carbonise power generation across Europe and the North Sea is a shallow sea, two thirds of it no deeper than the height of Nelson’s column. Hence the expectation of the Crown Estate, which leases land on the seabed, that 90 per cent more offshore wind will be installed there over the coming years to provide for the switch to electrical heating in homes and the charging of electric cars.

The fact remains that all this industrial capacity being installed has an ecological impact of some kind. How much space does a wind turbine take up? The actual footprint of wind turbines on the Dogger is a tiny fraction of the area. But then comes the levelling of the ground that takes place before piling starts which scoops up or bulldozes just the habitat that is starting to re-form. There are the rocks dropped as scour protection. Then there is the cabling, which needs to be dug in and laid under crushed rock to make sure it does not get swept away. Then there is piling, underwater noise pollution which will take years until construction is finalised. The world is undergoing two crises – a climate crisis and a biodiversity crisis – and attempts to tackle them both are under way on Dogger Bank. There are inevitable tradeoffs. Not everyone agrees that right balance is being struck.

Gannet on Dogger Bank, credit Charles Clover

Emilie Reuchlin wrote to the then UK Energy Secretary, Grant Shapps, in the summer asking him to stop the expansion of wind farms on Dogger Bank and to reserve these areas for nature restoration because the impact of wind farms was likely to be detrimental to nature recovery. Shapps’s fellow minister, Graham Stuart, Minister for Energy Security, sent a considered reply saying any the likely effects of any development on a number of “environmental receptors” – which he did not specify – would be considered by the Planning Inspectorate, with advice from the statutory nature conservation bodies before deciding to go ahead with three new farms. The recommendation, he said, would also include details of appropriate compensation where impacts could not be avoided.

This was not what Emilie was hoping for. She said: “I feel that in ten years we will look back and say it really shouldn’t have been done like this. We are not against wind farms. Just they have no place on the Dogger Bank, as this area is to become an engine for North Sea ecosystem restoration. Large scale industrial activities have no place within protected areas and the same goes for oil and gas development. We shouldn’t just replace one industry with another one. There needs to be space set aside for nature. That is what a marine protected area is supposed to do. The Dogger should be the beating heart of the North Sea once again. It could be the model for ecosystem restoration on a large scale with large predatory fish species, such as sharks and rays allowed to grow to maturity and the whole habitat reviving fish stocks and the entire ecosystem. We would like to see that as well as the development of more supplies of renewable energy outside of sensitive areas and MPAs – why is that impossible?“

Wind farm development on Dogger Bank, credit Charles Clover

It appears, after that exchange of letters and Rishi Sunak’s announcement at COP, that the die is now cast and that the largest wind farm in the world is going to be built on Dogger Bank. But does that mean that the argument about how the wind capacity is to be installed is over and the battle for biodiversity lost? I suspect that debate is only just beginning. The firm and graphic evidence from Doggerland’s expedition that prime locations for nature restoration and places where the seabed is starting to recover lie in the path of the advancing wind farms will be available to the developers and the statutory agencies when they are designing the next phase. Now people are watching, whereas before the seabed of Dogger Bank was out of sight and out of mind. It is too much to expect that the official bodies and the wind developers can get together and work out how to tread sensitively on the basis of that accumulating knowledge? They do face a legal requirement to use “best available technology.” And MPAs, when left undisturbed, are a net store of carbon emissions, and disturbed sediments are a source of greenhouse gas emissions, so that is a worthwhile aim. We have found wind developers very willing to do things with the grain of nature before – if it can be explained how.

Where was the art of the possible now, I wondered. Was there not an opportunity to find ways of doing enhanced restoration – perhaps the re-introduction of reef-building species – in these places as part of the compensation regime, which so far hasn’t delivered very much? That is a conversation to be had before these new wind farms are installed. As is the conversation about where, specifically, the space for nature is to be created on Dogger Bank, so it isn’t just an industrial landscape. That seems possible too. Where there seems much less justification is the installation of further fossil fuel activity in protected places such as these. A recent report found that nearly 30 per cent of the licences awarded to develop or explore oil and gas resources in UK waters had been given within marine protected areas. What contribution does that make to tackling either of the twin crises of climate and biodiversity we now face? Can it any longer be justified?

We did not have time to speculate further that night. There was another blow coming and we took a consensus decision to retreat, as the next time the sea would be calm enough for surveying was some days away and we could not stay out that long. The wind was rising but it was fortuitously at our stern and so we decided we would let the storm blow us back to port. The satellite phone had stopped working. My ear patches were wearing off and I was seasick: time to replace them. But it was a shame not to stay. There was so much still to do, more transects in other places including where Greenpeace had dropped the boulders that forced the British government to take the protection of Dogger Bank seriously. All would now have to be done next year. We spent Wednesday steaming back to Lauwersoog. A karaoke session with the crew after dinner raised the spirits and got over our disappointment at having to curtail the trip. We arrived in port around midnight, or just into Thursday morning, November 30. We had seen for ourselves some heart-warming signs of recovery within a damaged ecosystem and we had asked some searching questions about the future. We had not found all the answers. But we would be back.

Save the Date:

Rewilding Dogger Bank – a panel discussion presented by Blue Marine Foundation and EA Sustain, Sunday, 14 January, 11 am – 12 pm

Speakers: Blue Marine co-founder Charles Clover, Blue Marine Chief of Legal Affairs Tom Appleby, Doggerland Foundation co-founder Emilie Reuchlin, archaeologist Vincent Gaffney, with Moderator Joanne Ooi

In this panel discussion, members of the team that successfully pressured the UK Government to protect the UK portion of Dogger Bank will explain how they are parlaying their research and legal strategy into achieving similar protection for the European part of Dogger Bank, not least because it is the Atlantis of the North Sea, the flooded remnant of a land bridge to Continental Europe yielding invaluable archaeological evidence of ancient human civilisation, in addition to protecting endangered marine life.